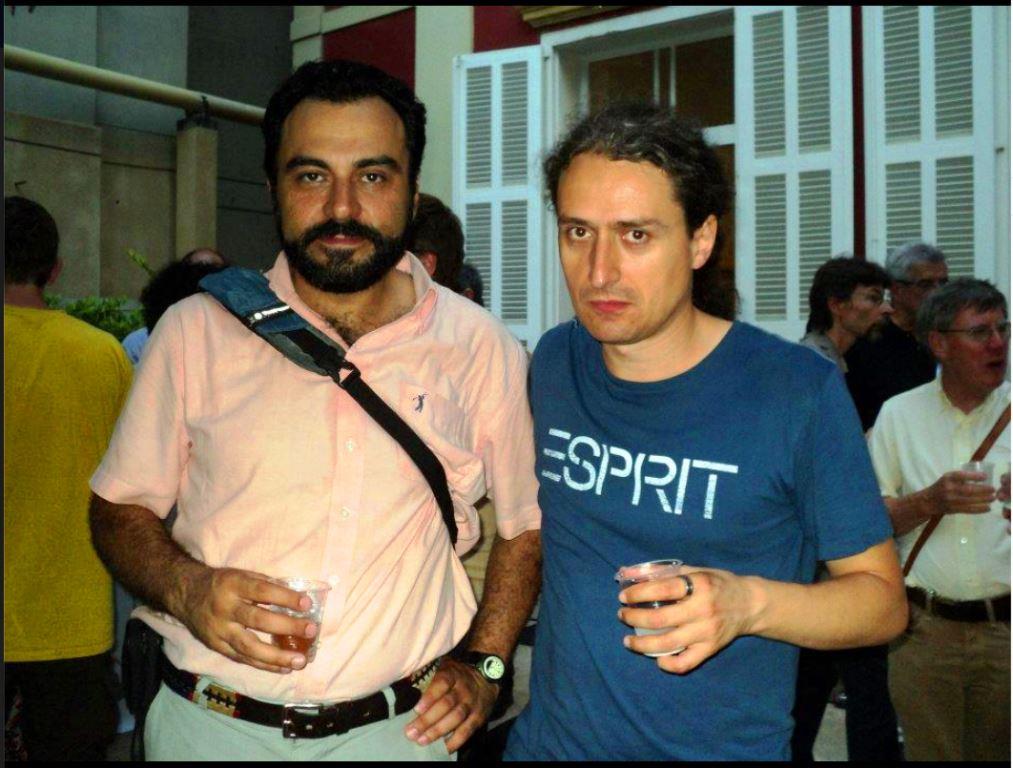

Andrés Bobenrieth with Alessio Moretti

3rd World Congress on the Square of Opposition

American University of Beirut, Lebanon, 2012

The Many Faces of Inconsistency

3) How do you see the evolution of paraconsistent logic? What are the future challenges?

A lot could be said about this, but I will focus on a few specific aspects. When I began to investigate these issues, it was said that the study of paraconsistent logic was just beginning and that there were many things to do and that they could shake logical and philosophical thinking. It has been more than 25 years in which an enormous amount has been written on the subject, but I have the impression that the predicted tremor has not been felt so much. The reasons for this may be many, starting with its perhaps being still too early to affect 25 centuries –at least– of a very established tradition of defending consistency, but my impression is that, except for those who have worked in paraconsistent logic and paraconsistency (which I think are not the same, although obviously they are related), the option of accepting explicitly and openly inconsistencies does not go beyond being a "curious" or even "interesting" option, and has never really taken very seriously or in depth. Considering that this interview will be read mainly by people working in paraconsistency, I am going to make a controversial statement: in my opinion the defense of dialetheism has done no favors to the paraconsistency outlook, because it has become an extreme position that is attacked by many, generally distortedly, and has ended up suppressing a more substantive discussion about the best way to deal with inconsistencies. In the Anglo-Saxon philosophical world, I have many times seen it pointed out as a possible position on various issues, but it ends up being a cliché to say that that "crazy idea" remains an extreme position. In fact I heard Kripke (in Oxford in 2001) refer to it and then disqualify it immediately by saying "I do not read such things". On the other hand, I do not see that much has been contributed by the reiterated affirmation that "there are true contradictions", the liar sentence (and its variants) being the foremost paradigmatic example. In my opinion, it is much more interesting to reflect and work on the theoretical and practical options that are located in the interval that has at its endpoints the classical and the dialetheist positions. The question should not be: "inconsistencies yes or no?", but which ones, how and where.

A lot could be said about this, but I will focus on a few specific aspects. When I began to investigate these issues, it was said that the study of paraconsistent logic was just beginning and that there were many things to do and that they could shake logical and philosophical thinking. It has been more than 25 years in which an enormous amount has been written on the subject, but I have the impression that the predicted tremor has not been felt so much. The reasons for this may be many, starting with its perhaps being still too early to affect 25 centuries –at least– of a very established tradition of defending consistency, but my impression is that, except for those who have worked in paraconsistent logic and paraconsistency (which I think are not the same, although obviously they are related), the option of accepting explicitly and openly inconsistencies does not go beyond being a "curious" or even "interesting" option, and has never really taken very seriously or in depth. Considering that this interview will be read mainly by people working in paraconsistency, I am going to make a controversial statement: in my opinion the defense of dialetheism has done no favors to the paraconsistency outlook, because it has become an extreme position that is attacked by many, generally distortedly, and has ended up suppressing a more substantive discussion about the best way to deal with inconsistencies. In the Anglo-Saxon philosophical world, I have many times seen it pointed out as a possible position on various issues, but it ends up being a cliché to say that that "crazy idea" remains an extreme position. In fact I heard Kripke (in Oxford in 2001) refer to it and then disqualify it immediately by saying "I do not read such things". On the other hand, I do not see that much has been contributed by the reiterated affirmation that "there are true contradictions", the liar sentence (and its variants) being the foremost paradigmatic example. In my opinion, it is much more interesting to reflect and work on the theoretical and practical options that are located in the interval that has at its endpoints the classical and the dialetheist positions. The question should not be: "inconsistencies yes or no?", but which ones, how and where.